|

Just

as she is R.L. | The Economist – September 22, 2016 Bridget Jones: woman of substance, top news producer, millennial icon.

Prospero

doesn’t know anyone that has mistakenly turned up to a garden party

dressed as a Playboy bunny – or indeed spent time in a Thai prison for

accidental drug smuggling – but there is little point denying that Ms

Jones is one of the few truly relatable characters to have graced the

silver screen. When she emerged from Ms Fielding's column in the Independent in

the 1990s, she was a relevation. She was one of the first

female characters to agonise over her weight, her relationships, her

fashion choices and her career. She knows that she cannot help but

disappoint her mother, make painful social blunders (telling “Horatio”

that his opinions are “the sort of rubbish you’d expect from fat,

balding, Tory, Home Counties, upper-middle-class twits”) and experience

culinary disasters. She finds love and loses it. She pretends to forget

the name of her ex-lover’s new partner. Many young women can empathise

with the appeal of a cad like Daniel Cleaver or a stiff drink and some

mopey ballads on a lonely night. Bridget Jones is alive to feminism's

promise of “having it all”, but finds that the reality on the ground

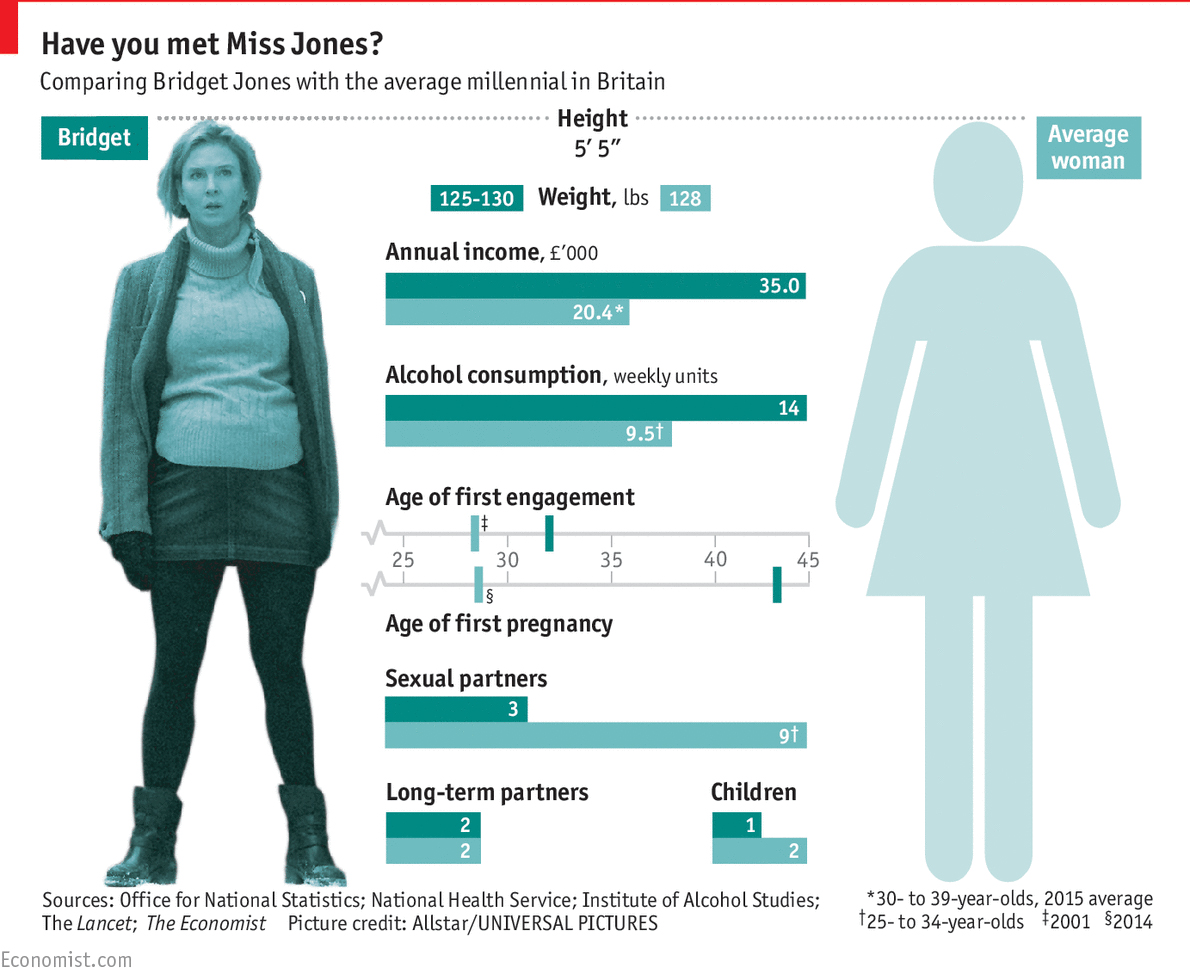

is far different. Data show that Renée Zellweger’s character is in many ways representative of the average woman in Britain (see chart). Though she drinks more (half a bottle of wine more per week), earns more as a “top news producer” and takes fewer “men for [her] own pleasure”, she matches the physical blueprint of the everywoman exactly. While the average woman gets engaged at 28, her engagement to Mark Darcy came at 32 and her first pregnancy took place much later (Emma Thompson, who is brilliant as the gynaecologist in “Bridget Jones’s Baby”, repeatedly refers to her as a “geriatric mother”, much to Bridget’s horror). The accidental nature of her pregnancy is common – Bridget uses out of date “dolphin-friendly” vegan condoms – the Wellcome Trust estimates that one in six pregnancies in Britain are unplanned.

“Bridget

Jones’s Baby” drags this luckless lady into the modern world of

algorithms, polyamorous relationships and Instagrammed meals. She curtly

reminds her farcically conservative mother – whose campaign for the

local parish council proudly announces that she supports “most Italians

and gays” – that even the most unconventional families deserve

acceptance. She shuns technology in favour of real experiences and

emotions, stands up for herself in a workplace which “celebrates the

inane” and vows to her unborn child that she’ll do her best. Millennials

could do a lot worse than Bridget Jones.

|